Filipino nurses have been recognized the world over as some of the best in their field, owing to the fact that Filipinos are naturally caring.

However, not all nursing students end up pursuing a career as a nurse—no matter how “lucrative” the pay may be once you make it outside of Philippine air space.

Some end up creating gaming videos for a living—like popular gaming content creator Gian Lois Concepcion, better known as GLOCO Gaming. Not every nursing graduate, though, is presented with a similar opportunity.

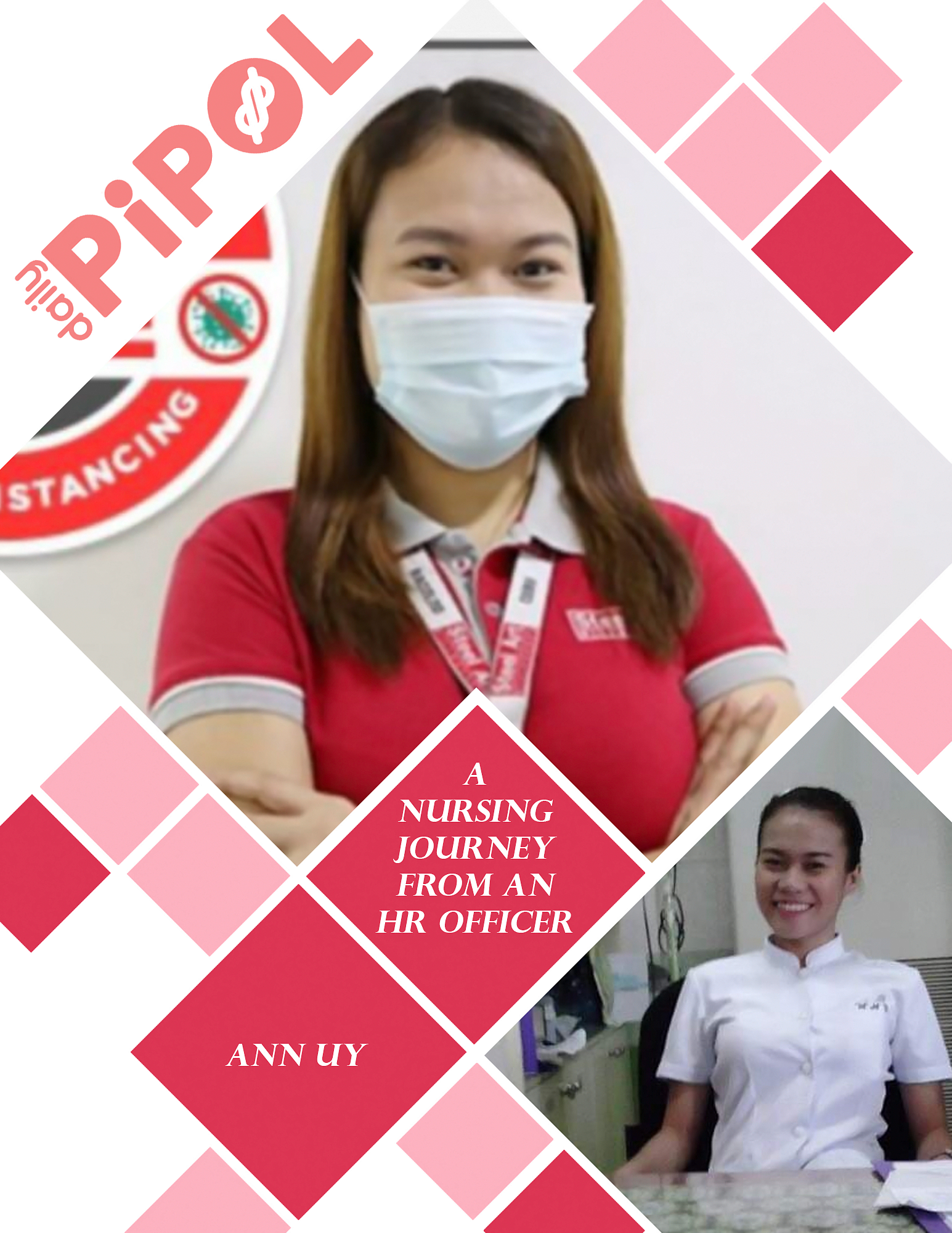

Take Ann Uy. She a human resources officer at a company in Metro Manila.

Yes, her current profile photo shows her as a nurse—complete with a stethoscope—but she no longer works as a nurse.

In her profile picture description, Ann says she has been peppered by the usual career-related questions as a nursing graduate, which includes why she isn’t a nurse at this moment.

Ann’s tell-all post sums up her journey.

JoKoy was right.

Ann’s journey starts off the same as possibly many Filipino nurse out there: she was told by her parents that nursing is a good degree to have because you’ll make a lot of money as a nurse.

Yes, kind of what stand-up comedian JoKoy said in one of his skits.

She would later learn to love the degree she took up. She said she’s fond of anatomy and physiology—lessons from which Ann says will remain with her for the rest of her life. She did, however, say she did not take as well to pathophysiology.

She would pass the board exam in 2015 and become a registered nurse the year after.

However, things started going south after applying for her first job.

Job hopping

Ann walked out from the first hospital she applied for as a nurse not as a nurse, but as an applicant.

During the application, the human resources officer she spoke to told her that she would need to undergo further training at their hospital. “You’ll be a trainee here for six months to one year.”She was also told there was a training fee she’d have to pay.

Things didn’t get better when she was told how much she would make in a month. “You’ll be paid P8,000 per month.”

Her reason for turning down the “offer”? All the time and money her family has spent just to put her through nursing school.

“My family spent five years and a lot of money just to help me get my degree. I should be helping them now that I’m a registered nurse—but I can’t.”

Since then, she’s taken a route that most registered nurses seem to take. She took a job as a call center agent to save up money so she can then practice her profession.

She would eventually be a nurse, though not in the hospital like she was expecting. “I’ve worked as a nurse for a construction company, in rehab, and in human resources.”

No regrets

She doesn’t regret the journey she’s taken. “Now, I work as a human resource officer and I’m loving every aspect of HR. I still deal with people like the patients I had before—just not the dying kind.”

She does, however, miss being a nurse.

She misses the feeling she gets when people tell her how much they appreciate her taking care of them. “I miss that satisfying feeling every time I see patients discharged from the hospital.”

She also misses being in the operating room, assisting and working beside some of the best doctors she has ever seen.

“Saludi at hanga ako sa mga passionate nurses diyan. May inggit ako ng very very light lang naman.”

The plight of nurses in the Philippines

Ann’s story as a nurse is just one of the many instances showing how tough it is to be a nurse in the Philippines—a fact now highlighted by the pandemic.

The government, led by the Department of Health (DOH), has sent out a massive call to all registered nurses in the country. The battle cry: we need your help.

Ann hasn’t escaped the call. She didn’t answer it, but she shared the offered and the working conditions she would be in.

“I have been contacted by both private and public hospitals. Someone even offered me P5,000 per day as a private duty nurse.” The catch: she needs to watch over a 60-year-old COVID-19 positive patient in the hospital.

Offers like these highlight the severe lack of value placed on nurses and nursing graduates in the country.

She hopes that in time, Filipino nurses would choose to work in a local hospital—but only if these benefits and policies are implemented: (1) above minimum basic pay for starting nurses, (2) monthly or daily hazard pay, (3) health and death insurance from the government, and (4) overtime pay.

“Yes, there are shifting schedules, but you won’t be able to do everything you need to do during your shift for all of your patients—not when one nurse is usually assigned to 40 patients,” she added.

Ann is but one of many nurses in the country that aim to fly overseas even if they do not want to. Hopefully, this pandemic has taught not just the government but Filipinos in general about how much we need nurses here in the country.